Well, since I was in the mood for writing about both videogames and the early-mid 2000s again, I thought that I’d take a look at one of the edgier years in the history of gaming. I am, of course, talking about 2003. Although, like any other year, there was a wide variety of games released in 2003, it definitely seems to be very representative of the “edgier” elements of the early-mid 2000s.

Whilst videogames had become more of a popular medium by 2003, they were – in the popular imagination at least – still somewhat associated with teenagers and twenty-somethings. Videogame culture at the time, from the magazines I remember reading back then, was still squarely aimed at these age groups, albeit less than during the late 1990s.

Also, although “violent videogames” controversies were more intense during the 1990s, they were still very much a thing in 2003. And, unlike modern controversies, games companies often seemed to be a lot less afraid of controversy back then. Not only did these controversies make videogames seem “rebellious”, but the extensive traditional media coverage of the time also served as free publicity too. It really was a different time in a lot of ways.

And there are at least four games which perfectly sum up the “edgy” gaming culture of 2003. Whilst I have technically played all four of these, some are games I’ve that only played small portions of many years ago, so I apologise if I write about some in more detail than others.

This article may contain SPOILERS.

First of all, let’s start with the edgiest game of the four – “Postal 2” (2003). This first-person perspective game focuses on an angry trench coat-wearing dude who has to run a series of mundane errands in a small US desert town. And, yes, the game’s story is basically just there as a pretext for the player to cause all sorts of chaos and destruction.

You can complete the errands in a normal and peaceful way…. but the game gives you lots of weapons, includes characters who try to fight you, allows you to do all sorts of tasteless/cruel things and also makes a “pacifist” run of the game deliberately slow and boring (via the use of long queues etc…).

Combined with a very cruel, crude and nihilistic sense of humour and a more immediate first-person perspective, this was a game that was pretty much designed to cause as much controversy as possible.

This is a screenshot from “Postal 2” (2003), showing one of the game’s more sophisticated and intelligent moments of satire. Not only do these “violent videogames are bad” protestors use violent rhetoric, but they also actually start shooting at the main character slightly later in the level too. Its a brilliant piece of ironic social satire and, again, surprisingly sophisticated for this game.

And, as a marketing strategy, it really worked. The game is more well-known for the notoriety surrounding it than anything else.

Objectively speaking, it isn’t the best first-person shooter game – especially by the high standards of its time. It looks a little low-budget and the gameplay is… functional, I guess. Plus, the game was released a little over one and a half years after 9/11, and it’s difficult to tell whether some parts of the game were satirising the paranoia and/or stereotyping that was common during this part of history or whether they were just reflecting it.

Yet, despite all of this, it is a game that you probably at least heard of if you grew up around computer games during the 2000s.

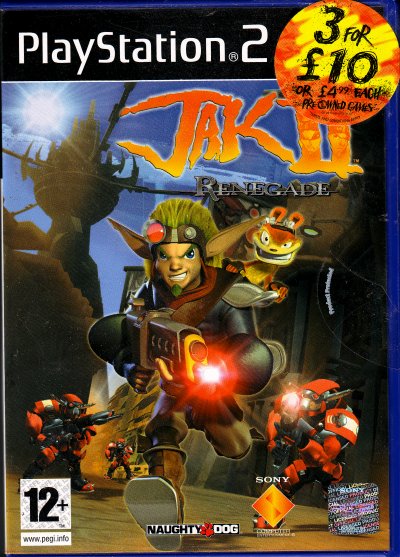

Secondly, let’s take a look at a milder – yet perhaps more symbolic – game from 2003. I am, of course, talking about “Jak II: Renegade”.

For context, the first game in the series – “Jak And Daxter: The Precursor Legacy” (2001) – was a fun cartoonish 3D platform game with pretty much universal appeal. Even though I only played it for the first time during my mid-teens in about 2004 – the gameplay, location design and humour were solid enough that I still really enjoyed it even though it looked like the sort of game that was designed for younger players.

This is a screenshot from “Jak And Daxter: The Precursor Legacy” (2001), a really fun and light-hearted cartoonish 3D platform game with solid gameplay and an almost universal appeal.

However, when the game’s sequel appeared in 2003, it was noticeably edgier in almost every way.

Although I really should re-play it sometime, since I got stuck on one part of it back in the day, the drastic increase in edginess is immediately noticeable even when you just look at the game’s box art:

This is the box art for “Jak II: Renegade” (2003). Everything from the main character’s “evil grin” facial expression (and goatee beard) to the fact that the main character is brandishing a gun, and the “12+” rating, show that this was a … much… edgier sequel. And, yes, I kept the price sticker on because I miss the days when second-hand PS2 games actually had sensible prices.

From what I recall of this one, it leans relatively heavily into its “edgier” style, featuring an angry/bitter version of the main character, a large gun that the main character can use, the ability to steal vehicles, some dystopian sci-fi elements, fantasy elements focusing on “dark eco” (an evil type of magical energy) and a few mild profanities during dialogue segments. Yes, it was aimed at younger players but it perfectly symbolises the edgier attitude towards game design during 2003.

The third game from 2003 is another “notorious” one. I am, of course, talking about “Manhunt”. Although I unfortunately only got to play a small amount of the PC port of it during the mid-late 2000s, this horror/crime game was something that was impossible not to have heard of if you grew up back then. It was that notorious.

Focusing on a death row prisoner who must kill other criminals for the sadistic amusement of an evil film director, this stealth-based game has a relentlessly grim and nihilistic atmosphere. And it caused one hell of a controversy when it was released, with the media blaming the game for a murder, political debate about the game in the US and bannings in a couple of countries. Not to mention that its 2007 sequel “Manhunt 2” had its own series of prominent censorship controversies too – even actually being banned in the UK for about a year or so at one point.

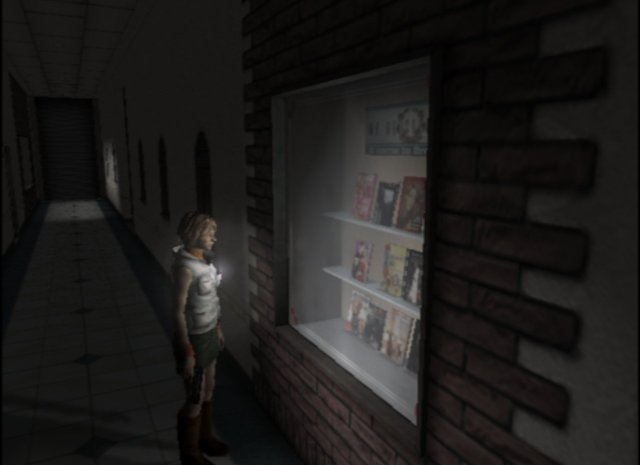

Finally, we’ll end with something a bit more subtle. I am, of course, talking about the 2003 survival horror game “Silent Hill 3“. Although this game is a lot more subtle than the other three games mentioned on the list, it was – like its predecessor “Silent Hill 2” (2001) – a complex and genuinely mature game which explored all sorts of themes that popular videogames of the time often avoided.

With a complex, well-written protagonist, this chilling horror game covers all sorts of serious subject matter – including bereavement, teenage pregnancy, religious extremism, romantic obsession etc… – yet, in the slightly fantastical context of the game, it is all handled in a surprisingly understated, intelligent and… mature… way. In a lot of ways, it is perhaps closer to the more “serious” type of “edginess” that is more common in modern games than in other games from 2003.

This is a screenshot from “Silent Hill 3” (2003) – a game which, along with its predecessor, was a genuinely mature game released during a time when “mature games” usually meant “appeals to immature teenagers“. It’s a more subtle game than the others on this list and was perhaps ahead of its time, in terms of its more “serious” attitude towards storytelling.

It didn’t cause controversy when it was released or shout from the rooftops about how “edgy” it was. Instead, in a surprising rarity for the time, it just told the kind of genuinely mature character-based story that – along with “Silent Hill 2” (2001) – is the perfect rebuttal to anyone who claims that videogames “aren’t art”. It was, in its own way, a rebellion against the popular idea of the time that videogames were just immature entertainment for teenagers.

———————-

Anyway, I hope that this was interesting 🙂